Doran, Martin & Zappavigna (2025: 58):

From the perspective of the model being developed in this book, the distinction between propositions (information) and proposals (actions) determines what can be negotiated in dialogue.

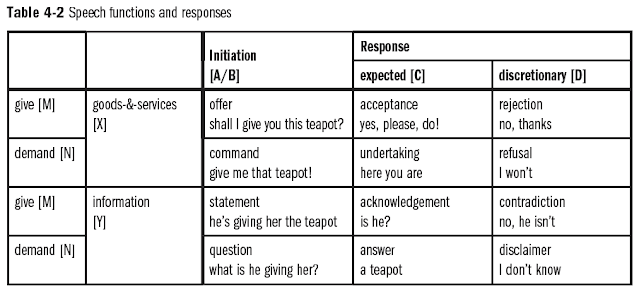

Looking from ‘below’ in terms of discourse semantics and lexicogrammar, proposals tend to be realised through action exchanges (Berry, 1981b; Martin, 1992; Ventola, 1987), goods and services speech functions (i.e. commands, offers and their responses (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2014)), imperatives and options in modulation (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2014). Propositions on the other hand tend to be realised through knowledge exchanges (Berry 1981b, Ventola 1978, Martin 1992), information speech functions (questions, statements etc.), indicatives (declaratives and interrogatives) and options in modalisation (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2014).

Reviewer Comments:

[1] This formulation reverses the logical order of dependency. In SFL theory, it is the commodity of exchange that motivates the semantic distinction between propositions (negotiating information) and proposals (negotiating action). The functions of giving or demanding goods-&-services versus information arise in response to interactional needs, not as preconditions that restrict what can be negotiated.

To claim that the distinction itself determines what can be negotiated treats it as a kind of system-internal governor of dialogue — a misunderstanding of how meaning is enacted. Semantic systems in SFL are mobilised to construe social activity, not imposed upon it from above.

This confusion reflects a broader slippage: the projection of analytic categories back onto the processes they were designed to describe. When semantic typologies are mistaken for causal mechanisms, we drift into a logic in which meaning potential appears to precede and constrain context — a reversal of the principle that semantics realises context, not the other way around.

In short: the proposition/proposal distinction is not a gatekeeper of negotiation, but a reflection of its semantic organisation.

[2] The authors claim to be “looking from ‘below’ in terms of discourse semantics and lexicogrammar” in order to describe the realisation of proposals and propositions. But this phrasing reveals a fundamental confusion about stratified semiotic structure.

In Systemic Functional Theory, looking from below refers to examining a stratum from the standpoint of the stratum beneath it — treating the higher stratum as content and the lower stratum as its mode of expression (Halliday & Matthiessen, 1999: 504). From this perspective, we can describe how a semantic category such as proposal is realised lexicogrammatically through systems like mood (imperatives, offers) and modulation (obligations, inclinations).

However, the authors contradict the logic of this perspective by claiming to be “looking from ‘below’ in terms of discourse semantics and lexicogrammar.” This conflates two distinct strata: discourse semantics, where speech functions such as proposals and propositions are located, and lexicogrammar, where systems such as mood and modality operate.

In effect, they name the correct perspective — from below — but frame it as if the semantic stratum is the lens from which they are looking. This inverts the logic of realisation: one does not “look from below” in terms of the higher stratum.

A clearer and theoretically consistent formulation would be:

Looking from below, we can examine how the semantic distinction between proposals and propositions — speech functions — is realised in the lexicogrammar via systems of mood and modality.

This preserves the direction of realisation, respects the distinction between strata, and applies Halliday & Matthiessen’s framework with fidelity.