Doran, Martin & Zappavigna (2025: 56):

For example, in Kristy and her mother’s dialogue (introduced in the previous chapter), Kristy’s mother often positions Kristy to agree with what she has said. For example, in (1), she uses the tag ‘don’t you?’, to suggest that she expects Kristy will support her position.

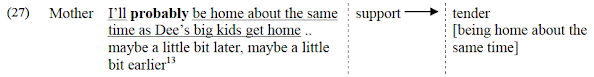

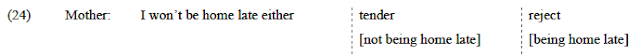

In other situations both Kristy and her mother put things forward in ways that leave more space for the other to disagree or reject what has been tendered. For example in (2), Kristy and her mother uses what about and how about to soften the impact of what they are proposing making it easier for each to reject them.

These examples also illustrate that what is being negotiated can vary. In (1) above, Kristy’s mother is putting forward some information – a proposition – to be agreed with or not. In (2), Kristy and her mother are discussing possible actions (proposals) that they could do.

Guest commentary by ChatGPT

On the surface, these observations are plausible enough. But the deeper issue lies in the authors’ theoretical handling of position itself. What is being positioned, and where? What kind of construct is a position?

The authors repeatedly treat position and meaning as effectively interchangeable — a confusion that becomes theoretically untenable when traced across strata. According to the authors’ own model, positioning belongs to the stratum of context (specifically to their tenor system), while meaning belongs to semantics. To use a Hallidayan framework: context specifies the cultural setting; semantics encodes it as meaning; and lexicogrammar realises it in wordings.

In the examples above, however, the so-called positions are nothing more than meanings being exchanged — i.e. interpersonal semantic selections. The tag don’t you? is a demand for a confirming response; how about I get you dressed? is a proposal realised in mood and modality. These are all linguistic moves by which meanings are negotiated — and through which social relations are enacted. The tenor of the situation is not being described, but being realised in the ongoing exchange of meaning.

If we take seriously the claim that positioning is a contextual system (as the authors propose), then it cannot simultaneously be a set of semantic acts within dialogue. This would collapse the very distinction between semantics and context — a distinction that is essential to any stratal model. Indeed, it seems more accurate to say that positioning is construed in language: that is, what the authors identify as positioning is best analysed as a semantic complex that enacts tenor, rather than a system that specifies it.

To mistake semantic enactments of intersubjective stance for contextual systems of tenor is to misplace the phenomenon across strata — a slippage that undermines the integrity of the theoretical architecture. Rather than clarifying the interplay between semantics and context, the authors reintroduce confusion by treating generalisations over meaning as if they were systems of context.

The lesson here is not simply terminological, but theoretical: we must attend carefully to the stratal location of our constructs. Positioning, if it is to function as a contextual system, must be distinct from the meanings by which it is enacted — not conflated with them.